What is the best linux distribution for you ?

There are various approaches to answering this question. The broad answer is: "any of them," but that's not very helpful if you're just looking for a place to start.

The problem is, there never can be one best Linux distribution for everyone, because the needs of each user tend to be unique. Telling someone who's looking for a good introductory distribution to try Gentoo, for instance, would be a mistake because for all its positive qualities, Gentoo is decidedly not a beginner's distro.

All too often, Linux aficionados will tend to list the distributions they like as the best, which is fair, but if they are not aware of their audience, they could suggest something that does not meet that person's needs. Finding a good Linux distribution is like finding a good match in an online dating service: good looks aren't the only quality upon which to judge a Linux distro.

To help users discover the Linux distribution that's best for them, this resource will definitively list the best candidates for the various types of Linux users to try. The use-case categories will be:

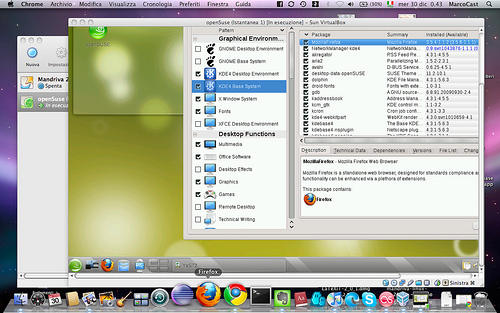

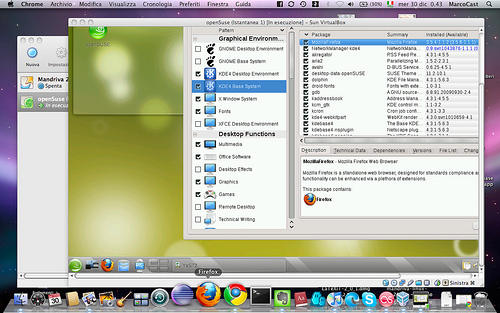

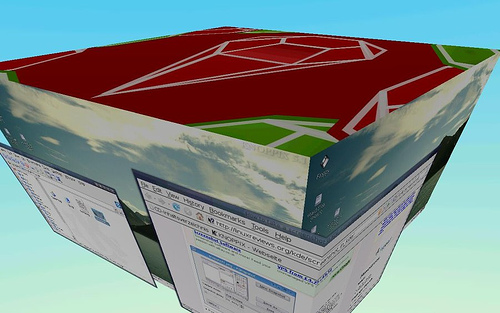

There are a lot of Linux distributions that have the primary focus of becoming the next best desktop replacement for Windows or OS X. Of all the categories in this list, this is the most sought-after, and contentious, group of distros.

While it would be ideal to include many distributions on this list, the reality is that there really needs to be just one "best" Linux distribution. For early 2010, that distro has to be Canonical's Ubuntu.

.jpg)

.jpg)

There are various approaches to answering this question. The broad answer is: "any of them," but that's not very helpful if you're just looking for a place to start.

The problem is, there never can be one best Linux distribution for everyone, because the needs of each user tend to be unique. Telling someone who's looking for a good introductory distribution to try Gentoo, for instance, would be a mistake because for all its positive qualities, Gentoo is decidedly not a beginner's distro.

All too often, Linux aficionados will tend to list the distributions they like as the best, which is fair, but if they are not aware of their audience, they could suggest something that does not meet that person's needs. Finding a good Linux distribution is like finding a good match in an online dating service: good looks aren't the only quality upon which to judge a Linux distro.

To help users discover the Linux distribution that's best for them, this resource will definitively list the best candidates for the various types of Linux users to try. The use-case categories will be:

- Best Desktop Distribution

- Best Laptop Distribution

- Best Enterprise Desktop

- Best Enterprise Server

- Best LiveCD

- Best Security-Enhanced Distribution

- Best Multimedia Distribution

There are a lot of Linux distributions that have the primary focus of becoming the next best desktop replacement for Windows or OS X. Of all the categories in this list, this is the most sought-after, and contentious, group of distros.

While it would be ideal to include many distributions on this list, the reality is that there really needs to be just one "best" Linux distribution. For early 2010, that distro has to be Canonical's Ubuntu.

.jpg)

Ubuntu edges out its closest contenders, Fedora and openSUSE, because its development team is constantly focused on the end-user experience. Canonical and the Ubuntu community have spent a lot of time and resources on bringing ease-of-use tools to this distribution, particularly in the area of installing Ubuntu and installing applications within Ubuntu.

In addition, Ubuntu's level of support for its desktop products is highly superior, which is important in this class of distributions since it is the most likely to contain users new to Linux. Both the official and unofficial Ubuntu documentation is robust and searchable, a big plus.

Best Linux Laptop Distribution

Laptop distributions almost fall into the same category as desktop users, but there are a number of key differences that make the criteria for evaluating a good laptop distribution important. Power management, docking tools, and wireless ease-of-use are critical to users on the go, as is having a distro that meets those needs.

Right now, the best laptop distribution is openSUSE, one of the lead contenders for the desktop honors. On the laptop, openSUSE shines with great connectivity tools, such as an easy-to-use networking toolset that not only handles WiFi connectivity, but also CDMA/cellular modem connections.

openSUSE also deals with docking stations for laptops very well, including dual-monitor management on the fly. Power management is very granular, which is great for detailing various power needs you might find yourself needing.

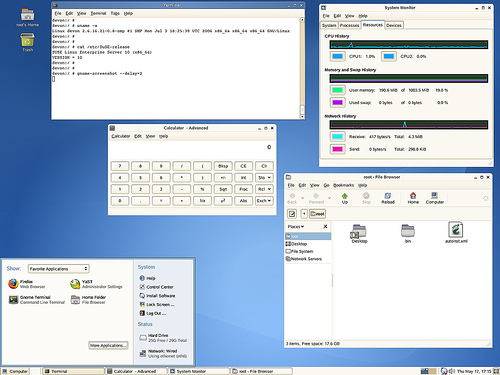

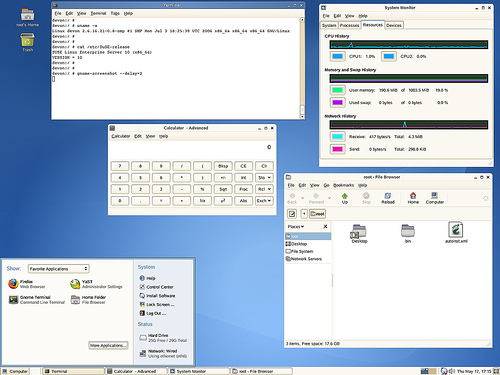

Best Linux Enterprise Desktop

This category is replete with great contenders as well, and it's difficult to highlight just one. At the end of the day, though, the nod must be given to SUSE Linux Enterprise Desktop (SLED).

The reason is simple: while SLED and its primary competitor Red Hat Enterprise Linux Desktop are nearly identical in features and support performance, SLED has the advantage of the openSUSE Build Service, a free and open service that lets applications be built and delivered to SUSE Linux and openSUSE products (as well as Red Hat and CentOS).

This is a very important differentiator in enterprise desktop development, as it means that SLED has the current advantage of application building and deployment in the enterprise arena.

Best Linux Enterprise Server

Again, in this category it really comes down to two main contenders: Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) and SUSE Linux Enterprise Server (SLES). Given the pick for the Enterprise Desktop category, you might expect SLES to get the "best of" label here.

But, when all factors for the enterprise server are weighed, RHEL is still the king of this particular hill.

Red Hat edges out Novell with its server product, because RHEL users get a deeply mature distribution, and Red Hat's support structure is second to none in the enterprise channels.

Best Linux LiveCD

As Linux technology improves, users can easily choose the LiveCD version of practically any of the Linux distros listed here to get the best LiveCD experience for their needs.

There is a specialized class of LiveCDs, however, that offers users utilities and tools for the specific purpose of repairing existing Linux and Windows installations. These distros are very useful to have regardless of what primary Linux distribution you like to use, because in a crisis they are invaluable to own.

In this class of distribution, KNOPPIX is hands-down the most complete and useful distro. Loaded on a CD or USB storage device, KNOPPIX will let you recover from nearly any rare Linux system crash as well as the much-less-rare Windows breakdowns.

Best Linux Security-Enhanced Distribution

Linux is inherently very secure compared to other operating systems, but there's always room for improvement.

One of the challenges for locking down Linux is if you are not careful, you can take away too much functionality. Another challenge is that the best security-oriented Linux distro, SELinux, is historically known to be difficult to configure correctly. Still, if security out of the box is your priority, this is the best place to begin.

Another approach is the white hat method: using security and forensic tools to examine your existing installation, determine the holes, then lock your system down based on what gaps you find. If you have the time and inclination, this is a great way to do it, because this will get any existing system more secure right away.

For the white hat approach, the best distribution is BackTrack Linux, a dedicated penetration testing distro that will enable you to safely try to crack any system you are caretaking. Its toolset and strong community give it the advantage in this category.

.jpg)

Best Linux Multimedia Distribution

General Linux distributions have come a long way in terms of multimedia performance. Rare is the audio or video file that can't be played on Linux. Music services such as Rhapsody and video sites like YouTube and Hulu are also standards-compliant and accessible to Linux users.

Still, for those users who are multimedia creators as well as consumers, there are Linux distributions that contain powerful tools for audio and video editing.

The best in this class is currently Ubuntu Studio. For audio, video, and graphic production, it contains a very complete set of tools, as well as format and codec support for a huge range of multimedia formats.

The applications contained in Ubuntu Studio are the same or similar to those used by major studios to create cutting edge work, so users are getting the best apps, coupled with the strong support ethos already found in the Ubuntu community.

In Linux there are as many opinions as there are lines of code. This represents one view of the best in Linux. Select yours.